Rewatching Dr. Strangelove

President Merkin Muffley

It’s been years since I last watched Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. Current events gave me a hankering to revisit it, so I rented the Blu-ray and popped it in last night. Some stray thoughts.

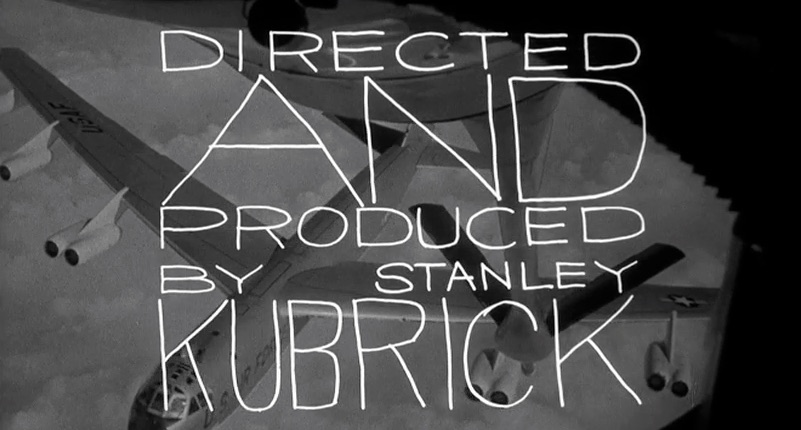

I’ve always remembered the overtly sexual mechanics of the film’s opening sequence, but I had forgotten Pablo Ferro’s beautifully designed titles. Over the years, graphic design has become a more central daily concern for me, so I sit in wonder of the gorgeous lettering. From card to card I stand mystified by the creative placement of each word. It feels at once perfect, everything in its place, and yet completely wrong, setting fire to common sense.

Pablo Ferro’s Titles

I was planning to add in a remark about how organic and alive these titles feel compared to the similar but much drier titles to Men in Black, but it seems those were done by…Pablo Ferro. Go figure.

One thing that feels so shocking by today’s standards is how compact Kubrick, along with Terry Southern and Peter George, manage to keep a narrative about the end of the world. If a film about an impending nuclear holocaust were made today, there would be at least one sequence where you see wide shots of public squares around the world reacting to the news. You would see people running in the streets. Or at the very least, given the secrecy of the scenario, scenes of happy life going on undisturbed. These sorts of macro scenes are crutches that help set the visual stakes. Dr. Strangelove brilliantly resists this urge, limiting itself to three main locations: Ripper’s base, the War Room1 and Major Kong’s plane, with only a brief moment in Turgidson’s mirror-clad hotel room. Kubrick gives the audience enough credit to understand the stakes.

I forgot just how good Peter Sellers is as President Merkin Muffley.2 His extended call with the Russian premier is one of the most brilliant bits of one-sided telephone. It’s Bob Newhart level good. I tend to think of him as Dr. Strangelove, desperately trying to control his right arm, but it is the Muffley role that, I would argue, requires a higher level comic genius.

Speaking of the good doctor, I noticed on this viewing that he is introduced at the exact halfway point of the film. I think he may appear in a single shot prior to that, but it is when his name is first uttered that he bursts into the film, changing the mechanics of the story. It feels as though the film’s title is a setup for a joke whose punchline is Strangelove’s entrée.

George C. Scott’s comic timing is a thing of beauty. He lands every single laugh. Line’s like “I’d like to hold off judgement on a thing like that, sir, until all the facts are in” and “He’ll see the big board!” could so easily be dry, but coming from him they’re centerpiece bits. I need to catch up on more of Scott’s films, but he is always a towering figure in anything I’ve seen him in. Even in a frothy picture like Not with My Wife, You Don’t!, he seems to work at one speed: intense.

It doesn’t have anything to do with anything, but it blows my mind a thirty-something James Earl Jones sounds exactly like an eighty-something James Earl Jones.

Another little something: “WORLD TARGETS IN MEGADEATHS.”

Something I never took note of before last night is the film’s visual effects. Any viewer can discern that they are looking at miniature aircraft superimposed over flying footage, but great care is taken to match the lighting conditions and movement of the planes to the background footage. The effect works well, perhaps better than audiences need it to. Kubrick, of course, was a detail-oriented filmmaker.

I forgot there is a comedic beat between when Slim Pickens takes his iconic ride on a nuclear missile and the film’s concluding “We’ll Meet Again” sequence. Another stroke of genius to have a room full of powerful men discussing, to the bitter end, the sexual Xanadu they could have created underground if only they had had the foresight. Kaboom.

I can’t quite figure out if Dr. Strangelove, a political satire steeped in the blackest cynicism of its era, is timeless or not. The film plays just as well today, but perhaps it is because the Cold War looms larger than we’d like to admit.

I hope I don’t wait as many years to revisit the film again. No doubt, I will find even more in it the next time around.

-

I feel like the ingeniousness of the design and use of the War Room set goes without saying at this point. One thing I noticed on this viewing is how smart the sound design is as we go around the table. When the camera is far away, so is the sound. It’s not a necessarily audacious choice, but it’s an important one that helps deliver some of the absurdities of the situation. ↩︎

-

Incidentally I also forgot how great the character names are. “Strangelove” is tame when put next to Jack D. Ripper. ↩︎