Exclusive: A Brief History

Ever since I picked apart coverage on The Verge, I’ve had the urge to go out and try to understand the word “exclusive,” whose use set off red sirens in my head for reasons I couldn’t articulate at the time.

I tried to describe it thusly last month: “To me…exclusive in a headline means more than just images, but analysis and original writing you won’t find anywhere else.” That was an oversimplification and at least one reader took note.

I’ve done a bit more thinking on the matter (in addition to research) and have come to the conclusion that the meaning of “exclusive” has been perverted to the point that it is basically useless. Allow me to share some of what I have learned.

The “Adverse Faction”

The Oxford English Dictionary lists many definitions for “exclusive.” For our purposes, lets go with the adjective under A.II.6.a:

In which others have no share, esp. of journalistic news or other published matter.

The noun form under III.B.4 is perhaps more instructive:

An article, news-item, etc., contributed exclusively to, or published exclusively by, a particular newspaper or periodical.

But the OED’s real charm, of course, is its citations. The earliest use of a journalistic “exclusive” they list is in the first issues of Punch, a humorous British weekly started in the mid-nineteenth century. Surely, though, this use predates it as Henry Mayhew’s brash magazine spent much of its inaugural year lampooning its dubious use elsewhere in printed media. Take this story filed in the August 28, 1841 issue:

AWFUL ACCIDENT.

Our reporter has just forwarded an authentic statement, in which he vouches, with every appearance of truth, that “Lord Melbourne dined at home on Wednesday last.” The neighbourhood is in an agonising state of excitement.

FURTHER PARTICULARS.

(Particularly exclusive.)

Our readers will be horrified to learn the above is not the whole extent of this alarming event. From a private source of the highest possible credit, we are informed that his “Lordship also took tea.”

And on and on joking about an inconsequential “exclusive” until:

THIRD EXPRESS.

Hurrah! Glorious news! There is no truth in the above fearful rumour; it is false from beginning to end, and, doubtless, had its vile origin from some of the “adverse faction,” as it is clearly of such a nature as to convulse the country.

In the December 4, 1841 issue, Punch takes more direct aim at a rival’s reportage:

“STUPID AS A ‘POST.’”

The Morning Post has made another blunder. Lord Abinger, it seems, is too Conservative to resign. After all the editorial boasting about “exclusive information,” “official intelligence,” &c. it is very evident that the “Morning Twaddler” must not be looked upon as a direction post.

Haven’t I heard this sort of media bickering elsewhere, recently? Ah yes, Gawker’s A.J. Daulerio sounded the same alarm this past Friday:

Today we’ve installed an editorial policy at Gawker which I hope will stick for some time: It’s about the word “Exclusive” being used in headlines and tags. It should be avoided at all costs, barring strange, unique circumstances wherein we feel it’s necessary to inform dumb readers that the story they are reading on this site was generated here and only here despite our dubious reputation as content remoras.

[…] This policy is not being put in place to undermine the work done here in the past; it’s more to prevent this site’s current iteration from adding additional levels of obnoxious dick-twirling often perpetrated by some other online gossip sweatshops that stumble upon BIG JUICY SCOOPS on an hourly basis because dimwitted celebrity horror shows just happen that frequently. I mean, seriously, you guys, just fuck TMZ in the mouth until they spit blood.

The word “exclusive” is nearly as old as big media rivalries,1 but it has never carried any sort of gravitas that those who like to slap it in a headline seem to think it has. For big egos and bigger brands, it has long been a tool for editorial oneupmanship, but for readers it has always been valueless.

Plants, Scoops and Leaks

William Safire, who captured the Nixon quote at the top of this article in his book, Before the Fall: An Inside View of the Pre-Watergate White House, is perhaps best remembered for his weekly “On Language” column in The New York Times Magazine. He had a gift not only for the intricate and difficult work of lexicography, but for boiling hundreds, if not thousands of years of knowledge and usage down to a few enlightening sentences.

In Safire’s Political Dictionary, he lays out the following definition under the entry for “plant”:

In current political usage, a LEAK is usually deliberate (as in Daniel Ellsberg’s massive leak of the Pentagon Papers to the Times), sometimes inadvertent (as in Undersecretary of State Richard Armitage’s offhand mention to columnist Robert Novak of the CIA Valerie Plame Wilson’s recommendation to send her husband to Niger to check out a tip about the sale of uranium ore to Saddam Hussein). A plant is always deliberate, and connotes “control” of the reporter’s story; an exclusive has a more legitimate ring, although reporters left out are envious; a scoop is dated slang for what is now a beat, which carries the least stigma of deliberate origination by the source, and usually means the reporter dug out the information by his own enterprise.

An “exclusive,” then, is just another way of saying a story has been planted by whomever wants it to appear in whatever outlet seems most beneficial to them. It’s Gordon Gekko calling The Wall Street Journal and saying “Blue Horseshoe loves Anacott Steel.” Like I said of The Verge last month:

How does one outlet get two non-starter exclusives from the same company in one week? The only conclusion I can think of is that Amazon is leaking them stories they want out there.

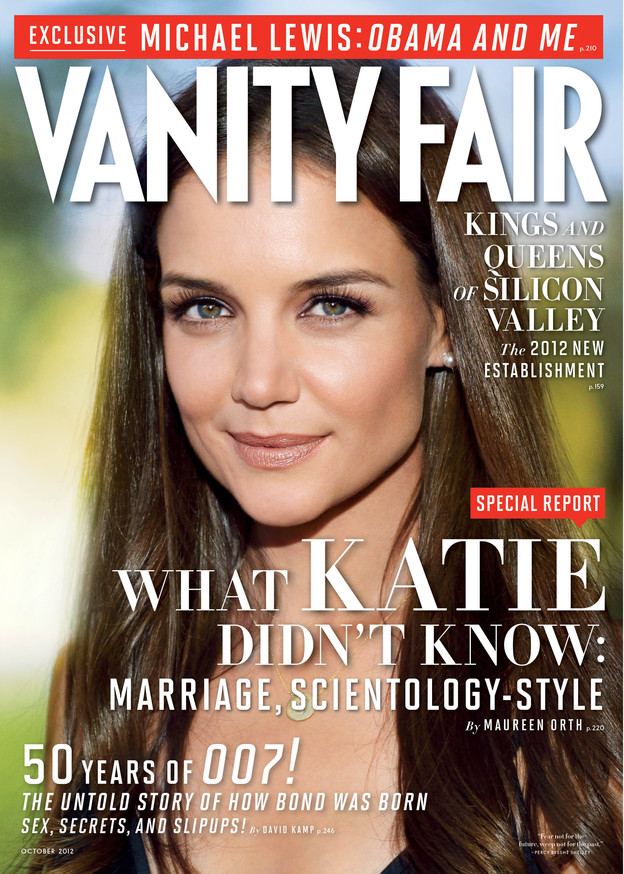

The October 2012 cover of Vanity Fair is instructive:

Vanity Fair October 2012

Michael Lewis was embedded with President Barack Obama for months, allowing him access to the man no other journalist could possibly achieve through regular means. It’s not just the resulting story that is exclusive, but the access granted to Lewis and all the strings that come with it, as reported by Jeremy W. Peters at The New York Times:

Like other journalists who write about Washington and presidential politics, Mr. Lewis said that he had to submit to the widespread but rarely disclosed practice of quote approval.

During a discussion at Lincoln Center on Monday night with Graydon Carter, the editor of Vanity Fair, Mr. Lewis volunteered to the audience that as a condition of cooperating with his story, the White House insisted on signing off on the quotes that would appear.

It doesn’t really matter where you come down on the validity of Lewis’s story; it is now a known fact that his source approved what appeared in print. This is what an “exclusive” looks like. A journalist and outlet was picked from among the many to reveal an otherwise unseen side of Obama. The “control,” as Safire would put it, was always in the hands of the source, not the journalist. Readers can be as discomfited as they like, these were the terms of what was clearly a mutually beneficial story.

Now let’s look at the other big story on VF’s cover. Listed as a “Special Report,” Maureen Orth’s article, “What Katie Didn’t Know: Marriage, Scientology-Style,” digs deep to reveal the lengths that Tom Cruise’s handlers went to find him a mate that wouldn’t embarrass the Church of Scientology.

Though private time with the President weeks before an election may be the weightier piece, Orth’s revelations required what most would consider grittier journalism. As Safire would put it, she dug out the information of her own enterprise. And yet her story, which no other outlet unearthed, doesn’t have “exclusive” in the headline. That’s because it would be in poor taste to gloat about what it really is: a “scoop.”

There is No Exclusive

This entire exercise, for me, has been to understand when and how to apply the word “exclusive” in my own work. After all, I’ve broken news here at the candler blog and at other outlets. I’ve never felt the need to write a headline with “exclusive” in it, even when the information I’m reporting is, in fact, unable to be found anywhere else. Am I doing it wrong, though?

At best, an exclusive is the result of a uniquely symbiotic relationship between source and journalist, with one extending a hand to the other for any number of reasons. It could be that the source wants to reach the widest possible audience, or a specific one, as in the case of Gordon Gekko and his man at The Journal. It doesn’t have to be all that nefarious, as in the case of Michael Lewis at Vanity Fair, whose access still told a compelling tale readers the world over are otherwise blind to, though one does have to wonder about what didn’t make the cut.2

At worst, the world of the exclusive is a dirty one in which media moguls use their brands and their checkbooks to battle it out publicly. In the entertainment world, a world I generally consider my beat, this plays itself out ludicrously on a daily basis, with outlets constantly reporting the same news as exclusives. No paper, tabloid or Web site seems ready to sit down and agree to terms for détente. And so the war trudges on, as outlets duke it out for readers and pageviews.

The truth, buried too deep for the average reader to care, is that “exclusive” is a holdover, a relic; the ink-stained wretches seem unwilling to let it fall to the wayside and their protégés and admirers seem fixated on letting the idiotic term find a home in our digital future. “Exclusive” is a way to dupe readers into taking you seriously, into believing that yours is the only page upon which they can devour the freshest and the latest. But that’s a lie. It always has been.

There is no great history to “exclusive” journalism. Ultimately, there is no exclusive journalism. It’s a term that was made up by publishers to nab an audience and further pirated by sources to communicate how best to spin the media in whichever direction they please.

So stop using it. All of you. Readers deserve better and this medium demands we provide it. Eventually they will flock elsewhere, where the stories are more substantive than the headlines.

Note: Some of the links in this story point to Amazon.com. These are affiliate links, and using them to shop for goods will support this site and the independent writing that appears here. I thank you in advance.

-

Which I would approximate starting in the early eighteenth century when Benjamin Franklin strong-armed his way into the publisher’s seat at The Pennsylvania Gazette, as described in Walter Isaacson’s excellent biography. ↩︎

-

Lewis claims only about 5% of what he witnessed couldn’t be published. Of course, that 5% could well be a bombshell; we’ll never know. In defense of this arrangement, Lewis may well have witnessed matters of national security what would endanger Americans abroad; the White House may have simply been trying to prevent such a slip, not cover up a scandal or obscure a conspiracy. ↩︎